Asia

A new Marxist president in Sri Lanka follows regime change in Bangladesh

By: John Elliott

Regime change has come to South Asia for the second time in a few weeks with the election yesterday in Sri Lanka of a Marxist president, whose party has not held the office before. This peaceful transfer of power follows the ousting in Bangladesh last month, after violent demonstrations lasting weeks, of Sheikh Hasina, who had been an increasingly controversial prime minister since 2009.

Both changes potentially increase China’s influence and underline the dichotomy of India losing power and influence with its neighbors at the same time as it is increasingly recognized internationally as a rising global and economic power.

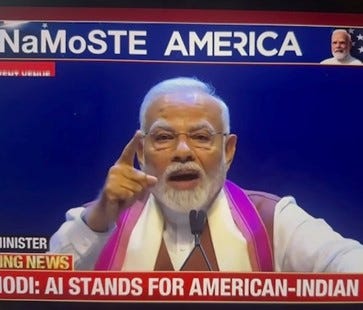

Just as Anura Kumara Dissanayake, leader of the leftist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), was claiming victory in a second-stage run-off of Sri Lanka’s presidential election, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi was riding high in the US, meeting President Joe Biden and other world leaders. Modi was at the four-nation Quad grouping with Biden and the prime ministers of Australia and Japan. He also had talks with the US president, boosted his domestic political profile by addressing thousands of Indian Americans in New York, and will be at a United Nations conference today (Sept 23).

Dissanayake’s JVP (People’s Liberation Front) was on the fringe of Sri Lanka’s politics for decades, adopting anti-American and anti-India lines at various times. In the 1970s, it led protests against the US over the Vietnam War and operated underground after being banned then and in the 1980s. Since the early 2000s (when Dissanayake was briefly a government minister), it has been involved in mainstream politics and is now part of the National People’s Power (NPP) coalition.

Its primary policies are anti-corruption and tax cuts and at times in the past it has criticised Sri Lanka’s debt crisis caused by Chinese investment. At his swearing in, Dissanayake said Sri Lanka did not have any geopolitical concerns and he was committed to whatever was in Sri Lanka’s best interests. “We need international help — so whatever geopolitical fractures exist around the globe, we will not be afraid to engage all in the best interest of Sri Lanka. We will work with the world”, he said.

Dissanayake succeeds Ranil Wickremesinghe of the United National Party (UNP), who became the president in 2022 after an economic crisis and mass protests led to the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, part of a powerful, controversial and corrupt dynasty.

It is expected that Dissanayake will now call parliamentary elections, and it seems inevitable that another South Asian government leaning towards China will be installed. Coming rapidly after what was virtually a coup in Bangladesh last month, when India lost its direct influence with the resignation of its close ally, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the Sri Lanka result is a double blow. Adding to its failures to deal with its neighbors, a pro-China government was elected in the Maldives earlier in the year.

That doesn’t seem to affect India’s role on the world stage, which has increased significantly in the past 10 years since Modi became prime minister.

Conversely, the more China strengthens its presence in the smaller South Asian countries, the more it is arguably necessary for the US and its allies to keep India as close onside as possible.

Biden illustrated his concerns about China’s regional role at the Quad meeting, where he is reported to have said (in what was supposed to have been a behind-closed-door meeting), that China “continues to behave aggressively, testing us all across the region.” That included South Asia.

There has been considerable speculation in India about whether America’s concerns led to it being involved in the ousting of Sheikh Hasina. This surfaced internationally last month but did not have much traction, though the possibility has been widely rumored in India. Yesterday it was set out in the Indian Express by Coomi Kapoor, a well-connected veteran columnist, who wrote that India was “realistic enough to trace the fingerprints of the US.” Yunus was “a close friend of the Democratic Party and of the Clinton Foundation”.

Referring to Chinese defense and infrastructure projects (and also to Russian involvement), she wrote: “The US was unhappy with Bangladesh for permitting the Chinese to build Asia’s largest submarine base at Cox’s Bazar and construct the Padma bridge. Russia’s funding of a nuclear power plant at Rooppur was another black mark against Bangladesh, which is near Myanmar, a military dictatorship with extremely close ties to China.” (The submarine base was a reference to a naval base China has been building to house two submarines that Dhaka bought from Beijing in 2013, and maybe to service other Chinese subs).

Kapoor added that Hasina had once claimed that US antagonism toward her regime was linked to its alleged (unsuccessful) efforts to gain a lease on her country’s St. Martin Island for use as a military base to monitor Chinese activity near the Strait of Malacca. This has been denied by the US.

More widely discussed have been Washington’s persistent criticisms of her autocratic regime, her rigged elections (the latest in January), the random imprisonments of opponents and critics, and the deaths of some 450 people during the student demonstrations that began in June and led to her downfall. Many observers however did not believe that these criticisms would lead to the US wanting to change a basically secular regime and risk Bangladesh becoming ruled by fundamentalist Muslim opposition parties.

Nevertheless, the speed with which the demonstrations escalated fed the rumors. In quick succession, Hasina fled at a few hours’ notice to India, Bangladesh’s army chief took over, and student leaders called for 84-year-old Yunus, a respected but controversial Bangladeshi Nobel Peace laureate, to lead the government. Yunus immediately flew to Dhaka from Paris, where he was watching the Olympics, and was installed as chief adviser of the government along with other advisers. It all seemed so rapid and seamless that it led to speculation in India about whether there was outside involvement.

No such suggestions are being made about the changes in Sri Lanka where India now needs to move adeptly to try to ensure that its substantial contributions to the vulnerable economy are valued.

Meanwhile, there are possible embarrassments waiting for Modi when he returns from the US involving Gautam Adani, India’s richest businessman and a close ally. Dissanayake has promised to scrap a wind power project funded by Adani, saying “this is clearly a corrupt deal, and we will definitely cancel it.” Bangladesh owes Adani Power US$500 million in unpaid dues for power supplied from an Indian plant which the new government says is one of various “opaque, expensive” deals it has inherited from Hasina.

John Elliott is Asia Sentinel’s South Asia correspondent. He blogs at Riding the Elephant.